The Mission Goes On

|

No shit, there I was somewhere over the Pacific, in the middle of night, heading for some thin strip of beach, on some remote island. My mission is to be the on site eyes and ears for the coming rescue force in two days. Because of the enemy forces, my BlackHawk helicopter and gun ships encountered, our extraction point is altered and things are quickly changing.

There wasn't much room to fast rope in, jungle on one side and ocean on the other. Last check and I exit for that thin strip of beach. Surprise, I find Tony Snodgrass and myself up side down under four feet of ocean. At the last second, the BlackHawk swooped and was gone. We were left trying to save our equipment, and lives. We had a mission to do and we had encountered enemy forces. We were lucky; our equipment was waterproofed and still operational. I wish we were!

Somehow we were able to evade the enemy and find our target. The American hostages looked okay, but were under constant guard. We were able to report vital information via SATCOM back to the commander in charge. With this information, a rescue plan was formed and the forces gathered. This was a large force of experts, including CCT, Delta, Rangers, C-130 and TF-160. The plan conducted under the cover of darkness was a two -fold operation. Send the Army teams in on helicopters to rescue the hostages. Some CCT would go in with them and set up ATC operations and prepare a runway for C-130 aircraft to come in and extract the hostages and U.S. Forces.

Simple, mission night shit was going great except we had one man down. Those darn Rangers in their excitement to get to the action pushed Mike Lampe right out of the helicopter at an extremely high altitude. Now, Mike didn't have a parachute and it just wasn't fair. He's the toughest SOB I know, but there were conflicting reports of his condition. Other than that, the operation was going off great, and the Delta teams had recovered the hostages.

Shit was happening everywhere, but we were ahead of schedule. I met up with Tim Brown , who took over ATC operations from me and after days, I could finally relax. NOT! As we were ahead of schedule, we thought we had control of the situation - NOT! I can still see the silhouette of that damned C130 landing on top of that BlackHawk.

Ten full minutes before any fixed winged aircraft are supposed to be in the area - SHIT HITS THE FAN! The operation was going so well, we were ahead of schedule. The Airborne Operations Commander decided to move the extraction up, but we were not notified. Due to a variety of incidents that didn't matter at the time we had a C-130 sitting on top of a BlackHawk. Somehow, I could see that C-130 flying off through the sparks of the disintegrating BlackHawk. I was on the SATCOM, and Tim was on the UHF, sorting this mess out. We had helicopters everywhere, one down and numerous C-130 aircraft minutes from landing.

In seconds, we were able to maintain control of the situation and prevent an impending disaster. We also had an aircraft down in the middle of nowhere. Tim Brown had the ATC under control and I went to the accident site to coordinate medivac. The BlackHawk was fully loaded with Rangers, a team I had just worked with. I recognized my comrades through the noises of disaster. It was pandemonium, but through it all professionalism saved the night. The Army was tending to the wounded and Tim Brown maintained control of the airflow. Together the wounded were treated and evacuated in minutes. Numerous lives were saved. Needless to say, it was a long night, but our training served us well. The Rangers suffered severe injuries, but all lived to fight another day.

We found Mike Lampe; he was a bit broken up, but alive. Now our only worry was the damaged C-130 that had Greg Capps and other CCT aboard. It had landed square on top of the BlackHawk rotors and had no landing gear. It was hours later that it finally made a safe landing on a foamed runway.

We lost a lot that night, but all lives were saved. If it wasn't for the quick and professional way Tim Brown handled this emergency, the operation could have turned into a huge disaster. I wanted to put Tim in for the recognition he deserved, but due to the classification of the operation, he went unnoticed (except for those in the know). Over the years, Tim has proven to be a valuable asset to CCT. Finally, I'd like you all to understand there's more to this man than you'll ever know. Thank you Tim, for your dedication and unending servitude. I Love You, Man

After months of hearings, it was determined the accident was a command problem and CCT had saved the night. Mike Lampe got to visit Hawaii, where they put him back together and made him even wiser, he won't get in front of a Ranger anymore. Today, this incident is almost forgotten, but not until Tim gets his recognition. HooYa! We were lucky this was only a training mission! ....................................................Mac

|

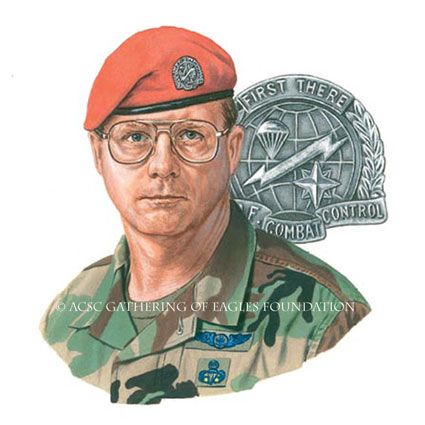

AIR COMMAND AND STAFF COLLEGE AIR UNIVERSITY CHIEF MASTER SERGEANT MICHAEL I. LAMPE WARRIOR, LEADER AND VISIONARY an excerpt

|

On 18 February 1985, Chief Lampe experienced a mishap during a Pacific Command military exercise on Tinian Island, Guam, which would challenge him physically and mentally. As part of a runway clearing team conducting a rotary-wing insertion onto a runway, he was inadvertently bumped out of the helicopter by another assault team member. The team had already been given the one-minute out warning call, thus the safety strap was removed and the doors were already open on the MH-60. The helicopter was approximately forty feet above the ground preparing to land on the airfield surface. Chief Lampe, now in unplanned free-fall with all his standard gear load-out weighing approximately fifty pounds, impacted the coral runway and embedded his left forearm approximately three inches into the landing surface with his weapon still in his hand. Additionally, he broke his wrist and his arm was at a ninety degree angle. Ironically, Lampe had told the commanding general hours prior to this exercise, “this exercise should be postponed, I don’t believe we’re ready for execution.” How intuitive and insightful this observation would bear out for the Joint Special Operations Task Force (JSOTF).

Fortunately, Carlos, a Special Forces medic, immediately responded to the emergency and “yanked his elbow and forearm out of the runway.” Chief Lampe stated “I don’t feel any pain, but get me out off the runway so an aircraft doesn’t land on me.” Carlos administered basic trauma response to control the pain and shock, while applying a splint to immobilize Chief Lampe’s left arm, which was initially held together by muscle and tendons. The critical aspect was to now get Chief Lampe to higher medical care that had advanced orthopedic capability. Unfortunately, there were several other personnel injured on the training evolution due to poor coordination between all units involved in the exercise. Catastrophically, the helicopter assault force never acknowledged a change in hit time, thus a MC-130 operating off the new hit time, attempted to land on the runway while helicopters were still on the landing surface. The MC130 attempted to land, despite not having communications with the Combat Controllers, was due to the blacked out box and one was operational. Standard operating procedures authorize aircraft to land in a no-communications situation with the control point provided the box and one lighting pattern is lit.

With the MC-130 striking a MH-60 during landing, there were numerous Rangers injured in the flipped helicopter. The rotor head sheared off and scattered debris and Rangers everywhere. Several Rangers were more critical than Lampe, so he waited for a USMC CH-46 to airlift him to Guam’s Naval Dispensary. He walked to the helicopter under his own power, but could not make it up the ramp. Once Chief Lampe arrived at the Naval Dispensary, the staff was not equipped or staffed to handle such an influx of critical patients, much less his massive injury. After initial triage by the surgeon, he told Chief Lampe, “I might have to cut off your hand,” which Lampe told him “just get me set and headed towards Fort Bragg.” Lampe chewed on a towel for seven hours due to the severe pain. The anesthesiologist believed Chief Lampe was going to die due to mistaking the camouflage on his face as burn areas. When Lampe was seen by the doctor, they drilled a hole in his elbow and ran a wire up his forearm and pulled his thumb back. He was too a point that he could be airlifted to the next higher medical care facility, Tripler Army Medical Center in Hawaii. Unbeknownst to Chief Lampe at the time, the medical staff did an outstanding job and inevitably set conditions for his eventual recovery and rehabilitation.

When Chief Lampe departed Guam, he was a patient in the DoD medical system. He arrived in Hawaii and was admitted to Tripler, however, Chief Lampe desired to go back to Fort Bragg and Womack Army Medical Center. Due to the amount of Special Operations personnel and 82nd Airborne Division paratroopers, Womack was deemed the premiere hospital for orthopedics. Additionally, Lampe knew the best surgeon on staff, so he wanted him to work on his shattered wrist and arm. Disregarding his patient status at Tripler, he left the hospital after learning that a C-141 re-deploying personnel from the exercise was transiting through Hawaii, so he headed to Hickam Air Force Base. Major General George Worthington was able to get Chief Lampe onboard the C-141 for the flight back to Pope Air Force Base, and medics onboard watched over him. Upon arriving at Pope, he drove himself over to Womack, and immediately sought out Doctor Nash to request his immediate attention to his injury. The surgeon laid into Chief Lampe due to atrophy and he should have remained in Hawaii due to the considerably longer delay in attention to his arm and wrist. Upon evaluation of the injury and the surgery required to repair Chief Lampe’s left arm, Doctor Nash speculated that Lampe would be medically boarded out of the Air Force.

The

surgery repaired and re- set his broken bones. He was told not to

expect full utility of his left arm, and his days of being a Combat

Controller were over. This did not sit well with Chief Lampe and

ultimately added fuel to his fire for a full recovery and to get back

on operator status. Through nine long painful months of physical

therapy with Specialist Cumaloski, a cute red-headed female, Lampe

achieved unprecedented results. He credits her for his full recovery

due to her lack of compassion and desire to see him succeed in

recovery. Chief Lampe regained full use of his arm and passed the

Combat Control physical ability and stamina test. The will and desire

to push through the pain for what he loved to do overrode any medical

assessment of his future. This is a testament to the heart and soul of

a true warrior and the perseverance to beat the odds. This same

attitude and demeanor is what Chief Lampe imparted on his troops and

joint military brothers.

|

|

MC-130E, 63-7785, AND THE DOUBLE SECRET Z TEAM |

| The Same Story From the Cockpit of the C-130 by Harold B. “Butch” Gilbert, Major, USAF, Ret. |

|

In the spring of 1985 with Capt. Frank Sharpe as the AC, and

myself as the NVG copilot, and Wayne Washer as the NVG safety pilot, and a top

notch crew consisting of Dave Smith (Nav), Ned Calvert, Eric Worles, John

Slepetz, Sam Garrett, Dave Frederickson and John Smith took off from RPMK to

Anderson AFB, Guam to participate in a JSOC quarterly exercise. These were exercises the 1SOS only

participated in once a year since they were mostly conducted in the contiguous

US, and it was a big commitment to send one airplane to the states for such a

big exercise. Fortunately for us, this

one was right in our back yard.

Also participating in this exercise was another MC-130E from

Hurlburt Field, the AC was Skip Davenport and Don James was the lead navigator.

Another new tactic was that as we approached the IP for the

airland part of the exercise, we were designated holding patterns to await

clearance for the approach to the airfield at

Upon arriving at the airplane we had one additional

surprise. The PACAF/DO a Brigadier

General would be on board to observe our NVG approach and landing at

We spun out of the holding pattern as the lead ship and set

up for the approach. Totally blacked

out, everything through the slow down, configuration and descent down the glide

slope on the

Immediately I heard on every frequency including guard,

“Mayday, Mayday, Mayday, WE HAVE A REAL WORLD EMERGENCY!!” We had just hit a Blackhawk helicopter that

was hovering over the landing zone. The

helicopter had not received the moved up TOA over their satellite network. We had literally just landed on its Jesus Nut

(the device which holds a helicopter rotor to the shaft) and drove the

helicopter into the landing zone, it crashed, totally destroyed. It turned out

later that they were on a different satellite frequency and never acknowledged

the new TOA. They also did not have any

NVG compatible lights working on the exterior of the helicopter.

Once stopped Frank directed to shut down engines 1 and

2. I grabbed the condition levers with

one hand and slammed them to feather.

Next I feathered 3 and 4 and hit the evacuation bell and got out of the

airplane. Everyone got out safe and

sound, the airplane was on centerline but was leaning to the left. Everyone got a ride off the runway except us,

we had to wait for a bus to come out and get us. Before we could call it a night we had to go

to the hospital and give blood and urine and get interviewed by the flight

surgeon.

Once back at the BOQ, it took about a week to get 7785 a new

pair of shoes and fix some sheet metal damage.

The rotor blade also sliced off about half of the left flap. I don’t remember much of that week; I was

pretty much drunk most of the time.

It was only a few months later that Steve Fleming was flying

7785 on a night low level mission in the Philippines when he took a M-16 round

in the SPR panel that caused an in-flight fire, but I’ll let someone else tell

that story.

Who you gonna call? HAWKBUSTERS!!!

V/R

|

|

MC-130E, 63-7785, |

| The Same Story From the JOC, TOC, & CCT; Command Center Anderson AFB, Guam |

|

A small group of CCT

were tasked to work Anderson AFB as a strip designated as a semi-permissive

environment (which is really no such thing, it's either permissive or not).

Some of us were tasked with ATC duties, and unfortunately General Steiner

decided to co-locate the JOC, TOC and CCT control point. It was cool because we

got to wear dungarees and such, but it was a pain because we had to ruck up all

equipment and were really sweated out (obviously much less than the TAC team on

Tinian). It was close to 100 degrees but it was only about 110% humidity, so it

was merely a wet heat so we were told to ignore it.

| NOW, FOR THE REST OF THE STORY by Sgt Mac and Butch

|

|

I think I may have had a few beers with Butch, it was a long time ago and as he was drunk most of the time, so was I. I do remember, Tim and I ran into the crew at a local establishment and between us we solved all the military problems. So why were we still on Guam?

We (my team) were the last to leave the accident site and on the flight back to Guam I was feeling pretty good about our reaction to the disaster. I was telling Charlie Tappero what a good job Tim Brown had done and suggested he be recognized and was told I had more to be concerned about? He told me about how shit rolls downhill and I'm at the bottom of the hill, the lowest ranking person in charge. Just as Butch was greeted on return to base, we were all drug tested too being Air Traffic Controllers. They were playing this by the book.

The next day we (my team) boarded a C-141 to return stateside, however our plane was stopped on the taxi way and they opened up the ramp. Some big wig and a few cops talked with the loadmaster, who called Tappero over, who called Tim and I over. Tim and I were removed from the aircraft with only the clothes on our back. Tappero wanted to come with us, but they wouldn't let him, so he gave us his credit card so we could make bail.

Instead of taking us to the stockade, they took us to base quarters and told us to be available. It's funny the things you remember, but the guy checking us in asked if I needed anything else and I said a coke. Tim Brown gave me a good slap across the face, and without any exchange of words, I just looked at the guy gawking at me because Tim had slapped me and said, "I meant a six pack of beer."

They were bringing in an Investigation Team and it seems Tim and I were the main serving. We were left to marinate for the feast and in the mean time we marinated our selfs. I do remember running into Butch and his crew. We had a good talk and as I said we solved all the military problems. We all knew the problems, but it was up to the investigators.

The investigators grilled us a couple times, so many times they overcooked us and decided not to eat us. Charlie was right about the shit rolling downhill, but this happened on an island and no matter how hard they pushed, the shit just wouldn't roll . Tim and I were exonerated and a few procedures were changed. The real cause of the accident was overlooked and lost in politics.

They released us to ourselves and we flew back to Ft Bragg by way of Hawaii. We stopped in to see our wounded warrior, Lampe. He was a bit beat up, but still on top of his game. He wanted Tim and I to take him back with us, but security was formidable. It took some General to finally break him out and send him home.

Just another day at work, I'm looking forward to what they throw at me tomorrow.................. Mac

Dear Sgt Mac,

By way of concluding my story, I need to relate the aftermath of the official investigation of that night on Tinian.

This is what we were told by a member of the accident board (USAF O-5 who will remain nameless). Never in USAF history has an aircraft crew been found totally exonerated by the accident board, except us. The official accident report was classified TOP SECRET and probably still is today. The blame went totally to the command element and the SATCOM operators who never confirmed the moved up TOA was sent AND received by all concerned parties (i.e. the Blackhawks helicopter).

The day after the accident a flight engineer went out with the accident investigation team and took some photos of the accident site. When he went back 3 days later to pick them up from the BX photo shop, they were gone!

6-8 months after the accident the squadron awarded us medals. Unbeknownst to us, our commander had submitted us ALL for Distinguished Flying Crosses. The medals for everyone except the Aircraft Commander were downgraded to USAF Commendation medals.

The entire 10 man crew felt so bad at getting anything regarding this failed mission, that we requested and received our medals privately in our commanders office. The Aircraft Commander received his DFC in front of the squadron presented by a senior AFSOC (2nd Air Division) officer.

I still stay in touch with most of the crew from that night, thanks again for closing the entire loop to this amazing story.

V/R

Butch