Granada is the smallest and southernmost of the Windward Islands in the

Caribbean, only 21 miles long and 12 miles wide. Except for the spice

plantations that produced a third of the world's nutmeg, there was not

much there in 1983. A medical school operated by investors in the

United States accounted for 15 percent of its total economy.

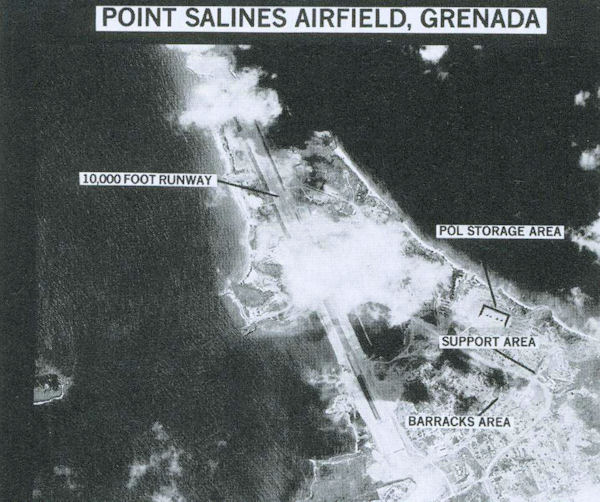

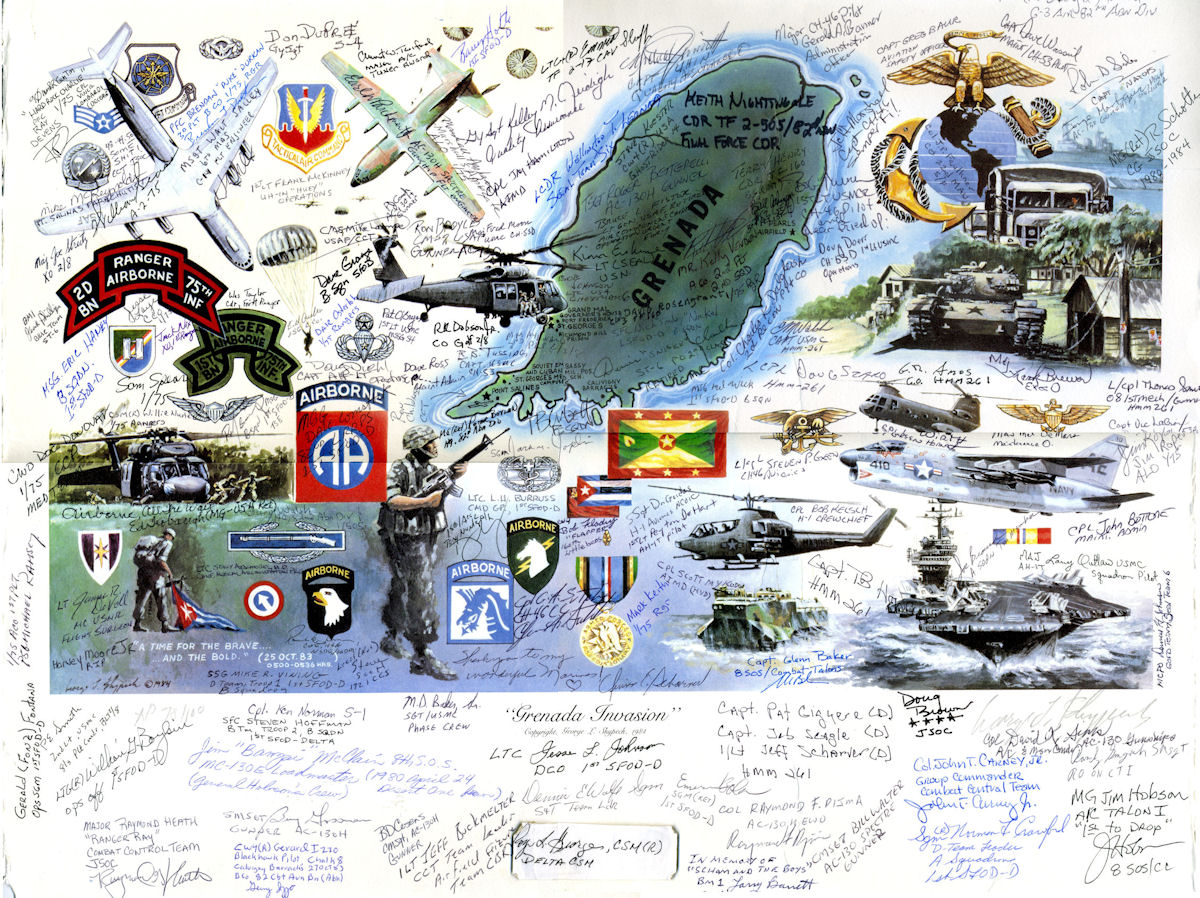

However, the little island nation offered several strategic benefits to the Soviet Union and its client state, Cuba. The leftist government in Grenada had given the Cubans permission to build a 9,000-foot airfield of military quality at Point Salines on the southern shore, and it was nearly complete. The airfield would give Moscow a staging base to support the Sandinista regime in Nicaragua and Communist insurgencies in El Salvador and Guatemala. For the Cubans, who could not fly nonstop to their operations in Africa, it would be a refueling base that avoided questions about landing in places where Cuban troops and military equipment were not welcomed. Revetments along the taxiway at Point Salines undercut the pretense that the airfield was for purposes of tourism. The United States was worried about the formation of a "red triangle" with Cuba in the north, Nicaragua to the west, and Grenada to the east. In a March 23, 1983, speech. President Reagan assailed "the Soviet-Cuban militarization of Grenada." Grenada's neighbors in the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS) were alarmed as well. Then, on Oct. 12, the four-year-old revolutionary "New Jewel Movement" government was overthrown in a bloody internal coup. The plot was conceived and carried out by even more-radical elements who wanted to move faster and harder toward a Marxist state. They executed President Maurice Bishop on Oct. 19. Gen. Hudson Austin, the head of Grenada's army, assumed control and ordered a round-the-clock, shoot-on- sight curfew. An Awkward Fit

In the US, Americans still had fresh and painful memories of the

1979-1981 Iranian hostage fiasco. It was a humiliating crisis in which

more than 50 US diplomats and staff, seized by revolutionary Islamic

elements, were held captive in the US Embassy in Teheran for more than

a year.

Thus, on short notice, the Pentagon organized Operation Urgent Fury to bring out of Grenada some 600 American students stranded at St. George's University Medical School. And since US forces were going in anyway, they would take advantage of the crisis to put the Grenada corner of the red triangle out of business. "The entire Grenada operation was driven by the State Department," said George P. Shultz, the hard-nosed Secretary of State who pressed Secretary of Defense Caspar W. Weinberger and members of the Joint Chiefs of Staff to move faster than they were inclined to do. "Weinberger said that we didn't know enough to act," Shultz said, but "we couldn't let the Pentagon drag out our preparations until it was too late, which I feared they might do." Reagan, who was already worked up about what was going on in Grenada, supported Shultz's call for a prompt response. When Bishop was executed, the Joint Chiefs sent a warning order to US Atlantic Command, alerting it to a possible need for a rapid evacuation. Under the unified command plan, LANTCOM had jurisdiction in the Caribbean and would be in charge of any such operation. It was an awkward fit for the Norfolk, Va.-based command; the Caribbean was strictly a sideline for LANTCOM, a maritime command geared toward offensive operations in the North Atlantic and reinforcement of NATO Europe in the event of a Soviet-led Warsaw Pact invasion. "We made an effort to evacuate the students through a Pan Am charter, but the plane was refused the right to land," Shultz said. "We made another effort by chartering a cruise ship. It was denied permission to dock." On Oct. 20, the original guidance for a possible evacuation was expanded to include "neutralization" of Cuban and local military forces in Grenada. Vice Adm. Joseph Metcalf, commander of the Second Fleet, was chosen to head the possible invasion force, and the Joint Chiefs assigned an Army officer, Maj. Gen. H. Norman Schwarzkopf, to advise Metcalf on ground operations.  The acting head of the eight-member

OECS, Prime Minister Eugenia Charles of Dominica, asked the United

States to intervene in Grenada. Her request was made on behalf of seven

members—Dominica, Montserrat, St. Lucia, St. Kitts-Nevis, St.

Vincent, the Grenadines, and the twin- island nation of Antigua and

Barbuda.

The eighth OECS member was Grenada, which had, in addition to a Marxist revolutionary regime, a governor-general. The office was a relic of Grenada's days as part of the British Empire. When the island in 1974 gained independence from imperial control, it became a member of the largely ceremonial British Commonwealth, and the governor-general was a symbol of the crown. Even after it seized power in 1979, how-ever, Bishop's revolutionary government declined to abolish the post of governor- general. It was occupied by an eminent Grenadian, Paul Scoon. While Scoon represented the queen on the island, he did not speak for British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher—a fact which soon would take on considerable significance. At the moment, Scoon was being held under house arrest by the rebels. He was, however, communicating with the outside world. Prime Minister Charles sent around to other OECS members a Scoon request for intervention. The governor-general followed up with a written request when he was free to do so. LANTCOM got the execute order on Oct. 22. Weinberger conferred full power to conduct the operation upon Army Gen. John W. Vessey Jr., the Chairman of the JCS, even though a Chairman was not normally in the operational chain of command. Congressional leaders were told in confidence of the impending action, but otherwise Administration officials gave out no advance notification. Certainly, they provided nothing to the news media, although invasion rumors were in steady circulation. Reagan later said, "We decided not to inform anyone in advance about the rescue mission in order to reduce the possibilities of a leak. ... We did not even inform the British beforehand because I thought it would increase the possibility of a leak." Although the main effort would be by US forces, small military contingents from Antigua, Barbados, Dominica, Jamaica, St. Lucia, and St. Vincent joined in the intervention. The plan was to quickly take and secure three main objectives: the Point Salines airfield, which was adjacent to the True Blue campus of the medical school; another airfield at Pearls, midway up the eastern coast of the island; and Government House, where the governor-general was being held, just east of St. George's city, the capital of Grenada. The Grenadian armed forces, consisting

of about 300 regulars and 1,000 militia, were no real challenge. They

were armed mostly with light weapons but had eight Soviet armored

personnel carriers and two scout cars with 14.5 mm machine guns. They

also had several kinds of anti-aircraft guns, but they lacked

radar-assisted fire control.

Two days before the invasion, Vessey's

attention and that of other senior officials was drawn away from

Grenada when terrorists in a truck loaded with explosives rammed into

the US Marine Corps barracks in Lebanon, killing 241 US service

members. There was some speculation that the Grenada operation was laid

on to distract attention from the losses in Lebanon, but preparations

for the intervention were well along by that time.

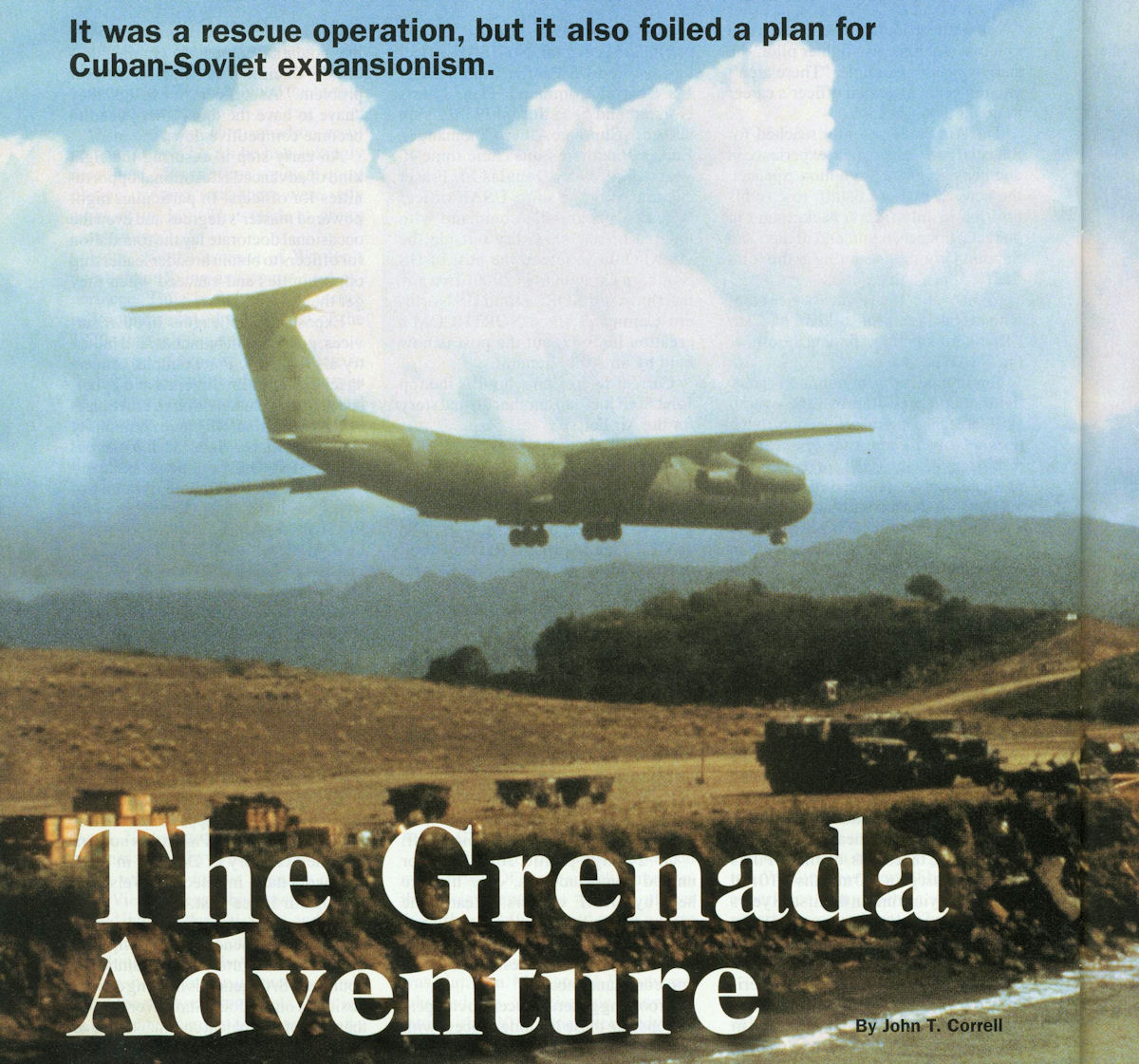

H-hour for the invasion—code-named Operation Urgent Fury—was 5 a.m. local time on Tuesday, Oct. 25. Army Rangers were to fly in and seize the Point Salines airfield. US marines, in a helicopter assault, were simultaneously to capture the other airfield at Pearls. More than a dozen US Navy warships—including Metcalf's flagship, the helicopter carrier USS Guam—were on station in the waters around Grenada. Air Force MC-130 and C-130E transports were in a holding pattern offshore, having picked up two battalions of Rangers before midnight at Hunter Army Airfield near Savannah, Ga., and refueled twice in flight to Grenada. The Marine Corps helicopter assault on the Pearls airfield went off on schedule at daybreak and met very light resistance. Defenses at Point Salines were more substantial. AC-130 gunship escorts passing over the field ahead of the airlifters discovered that the Cubans had blocked the runway with vehicles and various obstructions. It was not possible to land the transports, so the Rangers made ready to jump. The MC-130s came in elements of two. The first aircraft over the drop zone was flown by the squadron commander, Lt. Col. James Hobson. As he approached, he was illuminated by a spotlight from the island. AAA guns opened up from the nearby hills and 23 mm tracers were visible on both sides. To reduce their vulnerability to ground fire, the Rangers jumped from the very low altitude of 400 feet. They reached the ground in about 12 seconds. The Grenadian forces manning the AAA guns around the airfield were poor shots, but they managed to inflict some battle damage on the USAF transports before the gunships took the batteries out of action. The Rangers had cleared the runway by 6:30 a.m. and secured the strip shortly thereafter.  LANTCOM was wrong about the Cubans,

though. They fought fiercely, at one point charging the Rangers with

three BTR-60 armored personnel carriers. Fighting around the airfield

continued. In fact, two battalions of the 82nd Airborne Division were

flown in from Fort Bragg, N.C., by Air Force C-141s, to reinforce the

Rangers.

Meanwhile, Navy SEALs and Army Special Forces troops had run into difficulty at Government House and other sites around St. George's. Outgunned, the SEALs were pinned down along with the governor-general and his family until all of them were rescued by marines on the morning of Oct. 26. Elsewhere, Special Forces teams rolled up the opposition at several other locations. Just in Time Moving north and east from Point

Salines, the paratroopers found a cluster of warehouses at Frequente,

which were guarded by Cubans. The Cubans fled after an attempt to

ambush the oncoming Americans. The warehouses contained enough Soviet

and Cuban arms and military equipment to outfit six infantry battalions.

"Grenada, we were told, was a friendly island paradise for tourism," Reagan said. "Well, it wasn't. It was a Soviet-Cuban colony, being readied as a major military bastion to export terror and undermine democracy. We got there just in time." At 9 a.m., several hours after the start of Urgent Fury, Rangers arrived at the True Blue campus at the end of the runway at Point Salines. They rescued all of the American students that they found, but there were only 138 of them—far fewer than the number they expected to find. The other Americans—more than 200 of them—were at Grand Anse to the north and Prickly Bay on the southern coast. US intelligence had not known these facilities existed. It would take several days to collect all of the students, but eventually, 564 of them would be evacuated to the United States. Meanwhile, Navy A-ls mistakenly bombed a mental hospital on a hill overlooking the governor-general's house near St. George's city. The air planners and pilots had no military maps identifying the building as a hospital and Grenadian gunners were firing from that location at US helicopters and at the Navy SEALs pinned down in Government House. The Grenadians had given weapons to hospital staff and, incredibly, to some mental patients. The operation was beset with other problems as well. Army and Navy radios could not communicate with each other. The Rangers and airborne troops could see the ships offshore but had to send their requests for fire support to Fort Bragg, which relayed the messages by satellite to the ships.

Service parochialism also was at its worst. Schwarzkopf later reported,

"Admiral Metcalf received an urgent message from the office of the

Navy's comptroller in Washington warning that he should not refuel Army

helicopters because the funds-transfer arrangements had not yet been

worked out." Metcalf, declaring the message to be baloney (or words to

that effect), told his chief of staff, "Give them fuel."

In another instance, a Marine Corps colonel refused to transport Rangers to Grand Anse to rescue the students held there because, as the marine put it, "We don't fly Army soldiers in Marine heli-copters." He relented when Schwarzkopf threatened him with court-martial. These lapses would be cited as prime examples of organizational dysfunction in the debates leading to adoption in 1986 of the Goldwater-Nichols reorganization act, which established sweeping new rules for joint operations. They did not matter that much in Grenada because of the overwhelming strength of the invasion force. Significant resistance was over by Oct. 28, and the operation's combat phase ended on Nov. 2. Yet the structural weaknesses of the system were only too apparent. Forty-six-year-old Maj. Gen. Colin Powell, who was then Weinberger's military assistant (and later Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, national security advisor, and Secretary of State) called it "a sloppy success." Britain, which had pulled out of Grenada in some haste in 1974 amid strikes, rioting, and political turbulence was embarrassed by US intervention in a commonwealth nation. Thatcher, stung by an opposition Labour Party gibe that she was "an obedient poodle to the American President," angrily denounced the operation. Britain joined in a United Nations General Assembly resolution, adopted Nov. 2 without debate, "deeply deploring" the invasion of Grenada as "a flagrant violation of international law." Grenada's nearest neighbors and Israel voted with the United States against the resolution, which passed by a vote of 108 to nine. Charles R. Modica, the founder and chancellor of the Grenada-based medical school, observed the operation from school headquarters on Long Island, N. Y. From that safe location, he told the NewYork Times that the invasion was "very unnecessary" and that Reagan "should be held accountable" if anyone was hurt. In Congress, Rep. Thomas P. O'Neill (D-Mass.), the speaker of the House, criticized Reagan for resorting to "gunboat diplomacy." Vessey had reversed the no-press order on Oct. 28, acknowledging that it had been a mistake, but the operation was condemned by most of the American news media. Television cameras from all three networks were on hand when the first aircraft bringing students back to the United States landed at Charleston AFB, S.C., Oct. 27. The first student out fell to his knees and kissed the ground. A National Holiday

In a CBS poll conducted Nov. 3 in Grenada, 91 percent said they were

glad the US troops had come. Eighty-five percent felt they or their

families had been in danger, 76 percent believed that Cuba wanted to

take control of Grenada, and 65 percent thought the Point Salines

airfield was being built for Cuban-Soviet military purposes.

Almost 500 of the rescued students came to a reception at the White House Nov. 7, where they waved small American flags and cheered the President. On Nov. 8, with public opinion running strongly in favor of the intervention, O'Neill changed his mind, saying, "Sending American forces into combat was justified by these particular circumstances." A year after the operation, school chancellor Modica was among those attending White House ceremonies commemorating the anniversary of the invasion. He gave Reagan a small replica of a memorial set up on the True Blue campus to honor US troops killed in the operation. "I was probably the first person to voice reservations about your decision to go ahead with the rescue mission in Grenada last year," Modica said. "I know I certainly was the most publicized. During my State Department briefing the following day, I realized there were factors unknown to me which required that you make a tough and immediate decision.... The very definition of strong leadership is exemplified by your decisive action in Grenada."

About 8,000 US military members participated in Operation Urgent Fury,

along with 353 troops from allied Caribbean nations. It was essentially

a ground forces show, although 26 USAF wings, squadrons, and groups

took part. Between Oct. 25 and Nov. 6, Military Airlift Command flew

750 missions.

US casualties were 19 killed and 116 wounded. The Cuban contingent suffered 25 killed, 59 wounded, and 638 captured. The Grenadian forces sustained 45 killed and 358 wounded. The St. George's Medical School in Grenada reopened in January 1984. "The following April, a million rounds of ammunition were found under a false floor in the vacated Cuban Embassy," Shultz said. Also found were documents that revealed five military assistance agreements between the Bishop government, the Soviet Union, and Cuba, as well as a Moscow commitment to send some $30.5 million worth of military equipment and supplies. Austin, the rebel leader, was caught and given a death sentence, but he got a reprieve and instead spent the next 25 years in prison. Castro's man on the scene, Comas, escaped into the Cuban Embassy, where he was given diplomatic status and was returned to Cuba. Castro had him court-martialed and reduced in grade to private for his ineffective defense of Cuban interests in Grenada. The plan to establish a red triangle in the Caribbean failed. In December 1984, Grenada held the first free elections since 1976. The new Prime Minister was Herbert Blaize of the conservative, pro-US New National Party. In 2004, Scoon said Reagan had "saved us from chaos" and that US troops "came and established peace and the return of democracy, a democracy which we now enjoy.... It was not an invasion, because Ronald Reagan came to Grenada on invitation—invitation by me and invitation by the OECS territories." As for Thatcher's objections, Scoon said, "As governor-general, I owed no allegiance to the British government; I owed allegiance to the British crown. When you look at the end result, even the British people will now think it's a good thing the American and other Caribbean forces came when they did." Commentaries in the news media and opinion journals continued for the most part to depict Operation Urgent Fury as reprehensible and unnecessary. That view has not been shared on Grenada, where Oct. 25 is celebrated as a national holiday in remembrance of the US intervention.

Special Thanks to Fred Garcia Again

|