| A

Night to Remember

Combat Controller Performed Secret Mission To Desert

One Iranian Landing Site

Before

a C-130 or a helicopter ever touched down in the Dasht-e-Kavir, Iran’s

Great Salt Desert as part of a U.S. force to rescue 53 hostages in Iran,

an Air Force Combat Controller had been there and back.

Maj. John Carney,

the lead Combat Controller for Operation Eagle Claw, secretly performed a

reconnaissance mission to “pave the way” for the Desert One rescue

mission.

In March 1980,

Carney, nicknamed “The Coach” because he spent eight years as an

assistant football coach at the Air Force Academy, was “volunteered”

to check out the proposed landing site.

“I remember

Charlie Beckwith [the commander of the Army Special Forces team that was

to perform the rescue at the American Embassy in Tehran] volunteered me at

a meeting in North Carolina,” recalled Carney. “He said, ‘We

need a set of eyeballs on that site, and Carney ought to

go.’”

Not

too long after that meeting, Carney flew from Charleston, S.C., to Athens,

Greece, where he met up with his CIA transportation. In a small aircraft,

Carney and two CIA pilots flew to Rome and then to Oman.

On April Fools’

Day, Carney — clad in black Levi’s, a black shirt and black cap

— was secretly slipped into Iran to survey the Desert One landing site.

The site would be a pivotal forward staging area for the rescue mission.

Despite the stakes

and the circumstances, Carney said, “I was damn glad to get out of that

airplane when we landed.”

Their plane was

a decent size for three people, but not when they’re sharing it with

a fuel bladder and a fold-up motorcycle. The motorcycle was his ground

transportation.

Later Carney would

lead a six-man controller team into Desert One and witness the accident that

claimed eight American servicemen’s lives. But before any of that

transpired, Carney had to approve the site as a landing strip for the

operation.

Pictured; Mitch Bryant, John Koren, Mike Lampe, Bud Gonzales, Dick West, John Carney, Bill Sink, Rex Wollmann, and Doug Cohee.

Carney’s mission

was to install runway lights, take core samples and perform several other

tasks on the ground. His escorts were two CIA operatives who did this type

of thing for a living.

He’d have

one hour on the ground before the airplane left.

“It was the

shortest hour of my life,” said the now-retired colonel. “I had

so much to do and so little time to do it, I didn’t really think about

anything but getting the job done.”

The landing site

was next to a road. Carney would use the road to set up the landing strip.

He would march off a “box-and-one” landing strip. The corners of

the box, where he would bury the lights, were 90 feet wide by 300 feet. Then

the “one” light would be centered on the box and placed 3,000 feet

in front. The concept: land in the box and stop before the

“one.”

|

|

“As a football

coach, marching off yards was easy,” he said. What was hard was the

ground. “I had to use a K-bar [knife] to chip away the ground to bury

the lights.”

After setting up

the airfield, Carney went back to check his work. He discovered his escorts

landed in a different spot than they had discussed. Hence, the road, his

only orientation point, wasn’t where it was supposed to be.

One hour. After

that his escorts were out of there.

“There

wasn’t time to go back, and I wasn’t missing that plane out,”

Carney said.

If he missed the

plane, he had two options to get home. One was to walk. The other was to

use the Fulton recovery system. The system was an ingenious, albeit dangerous,

recovery device. The person needing rescuing puts on a harness — attached

to a wire, attached to a balloon. The balloon goes up and then a specially

equipped MC-130 swoops in, snags the wire, and whisks the person away.

Carney didn’t

fear being in Iran in the middle of the night, but he was afraid of the Fulton

“thing.”

“I was getting

on that plane,” he reiterated.

In his hour on

the ground, four vehicles drove past.

“It was

surprising,” Carney said of the vehicles. “All I could do was hit

the dirt. There’s not a whole lot of places to hide in a

desert.”

Carney had people

counting on him for his special mission.

“I was praying

that all would go well for John — that he would return safely with a

good report on Desert One,” wrote retired Col. James Kyle in his book,

“The Guts to Try.” Kyle was one of the lead planners and the on-scene

commander at Desert One. “One thing I was sure of — if anybody

could do it, John could.”

Out And Back

Carney made it out of Desert One, only to return 23 days later with the rescue

force.

When he left Iran

the first time, he was worried about the landing lights. But, after jetting

back to America on the Concorde, Carney said, “When I saw the satellite

imagery, it was a perfect diamond-and-one.”

Not quite the plan,

but it worked.

“I was happy

to see those lights come on,” said retired Col. Bob Brenci, who flew

the lead C-130 into Desert One. He was relying on Carney’s lights to

help him land in the Iranian Desert. They worked. He landed.

“He is a true

American hero,” Brenci said about Carney. “Crazy, but a

hero.”

Crazy, maybe, but

Carney said he’s no hero.

“I was just

doing what needed to be done,” Carney said.

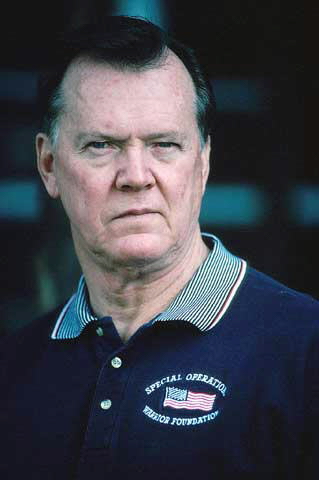

Today, Carney is

the president of the Special Operations Warrior Foundation in Tampa, Fla.,

a nonprofit organization that helps children who have lost a parent in a

special operations mission or training accident.

At 61, his hair

is a little gray, but he still looks like he could jump out of planes and

take down airfields. The former controller has a presence about him.

“He’s

a natural leader with tremendous charisma,” said Chief Master Sgt. Rex

Wollmann, the superintendent of the 22nd Special Tactics Squadron at McChord

Air Force Base, Wash. Wollmann has known Carney for more than 21 years. Their

first mission together was Desert One. “He’s the kind of guy

you’d follow anywhere,” Wollmann said of his former boss.

“Men like

Carney are worth a hundred planes or ships,” Kyle said.

Coach went on to

participate in operations in Panama, Grenada, the Persian Gulf War and others

he can’t talk about. But, he’ll always remember his

“volunteer” reconnaissance mission to Iran.

“It was the

shortest hour of my life,” he said.

|

In the wake of the Desert One tragedy, where eight American servicemen died,

17 children were left fatherless.

To ease these families’ pains and worries, two organizations were formed

to provide for these kids’ educational future. The Bull Simmons Fund

was founded to support the Air Force children and FLAG -- the Family Liaison

Action Group -- was founded to support the families of the hostages.

Over the course of several years these two organizations came together to

form the Special Operations Warrior Foundation.

For the past 21 years, this foundation, headquartered in Tampa, Fla., raised

money and awareness to educate children of special operators killed in the

line of duty, according to retired Col. John Carney, the foundation’s

president and chief executive.

"The warrior foundation enhances the sense of family within the special

operations community," said Brig. Gen. Richard Comer, Air Force Special

Operations Command vice commander. "Community is constructed in deeds and

not words. This foundation is a doer."

To date the foundation has helped 12 children earn college degrees. Another

37 students are enrolled in college with the foundation’s financial

support. And, another 362 children fall under the foundation’s umbrella.

I don’t think most Americans realize that every special operator is

a volunteer," Carney said. "Six out of every 10 special operators are deployed

at any given time. It’s important that they know if something happens

to them that their children will be educated."

That’s one of the main roles of the foundation. An insurance policy

for America’s silent warriors. An insurance policy born out of the tragedy

of Desert One.

"

|

For more information about the Warrior Foundation, visit its site at

http://www.specialops.org.

|

| MACOS, Dec 1982; Rick Caffee, Nick

Kiraly, Rex Evitts, John Scanlon, Doug Phillips, Mike

Lampe, Greg Capps, Dick West, Ray Heath, Johnny Pantages,

Jerry Bennett, Mike McReynolds, John Carney, Fran Oster, Wayne Norrad,

Chuck Freeman, Craig Brotchie , and Jerry Jones Support; Nick's

Man, Mr. John J. Rivers Jr. ; Supply Tightwad, Chuck

Talley, and on vehicles would be "Chocks" Rod Defigh; Radios, Don

Whitman; Rigger, Steve Miller who later cross-trained into CCT.

This is the whole team, minis Doug Brown & Dave

Lillico......... Sure has grown from our double wide trailer in theCombat Control Schools back yard, HooYa! |

|

|

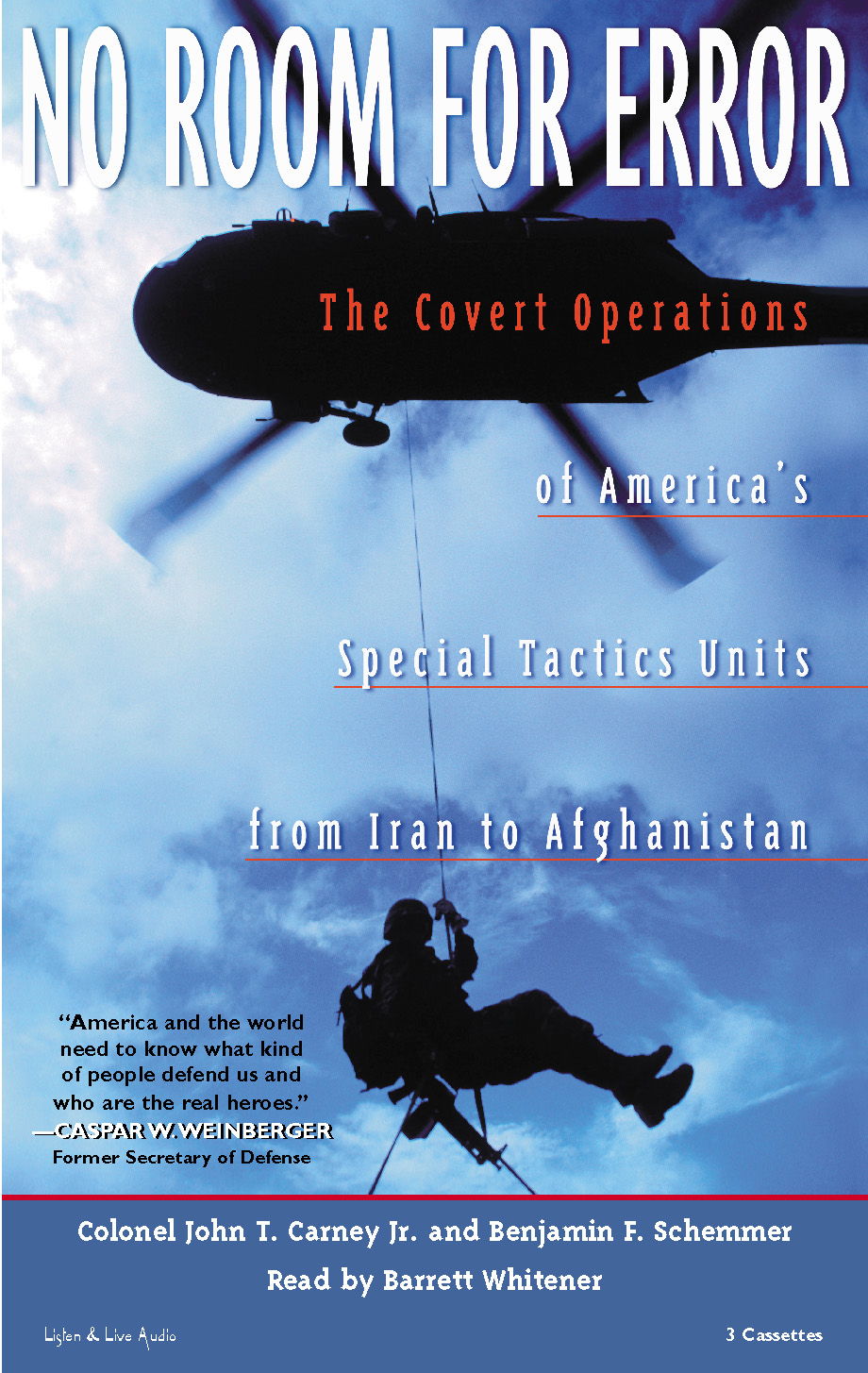

Purchase the Book;

No Room For Error, By John Carney

Part

memoir, part military history, No Room for Error reveals how Carney,

after a decade of military service, was handpicked to organize a small,

under-funded, classified ad hoc unit known as Brand X, which even his

boss knew very little about. Here Carney recounts the challenging

missions: the secret reconnaissance in the desert of north-central Iran

during the hostage crisis; the simple rescue operation in Grenada that

turned into a prolonged bloody struggle. With Operation Just Cause in

Panama, the Special Tactical units scored a major success, as they took

down the corrupt regime of General Noriega with lightning speed. Desert

Storm was another triumph, with Carney’s team carrying out vital

search-and-rescue missions as well as helping to hunt down mobile Scud

missiles deep inside Iraq.

Now

with the war on terrorism in Afghanistan, special operations have come

into their own, and Carney includes a chapter detailing exactly how the

Air Force Special Tactics d.c. units have spearheaded the successful

campaign against the Taliban and Al Qaeda.

Gripping in

its battle scenes, eye-opening in its revelations, No Room for Error is

the first insider’s account of how special operations are

changing the way modern wars are fought. Col. John T. Carney is an

airman America can be proud of, and he has written an absolutely superb

book.

http://www.amazon.com/No-Room-Error-Operations-Americas/dp/0345453336

http://www.randomhouse.com/catalog/display.pperl/9780345453358.html

http://search.barnesandnoble.com/No-Room-for-Error/John-T-Carney/e/9780345453358

|

|

|

A Mission Of Hope Turned Tragic. A Case Of What Could've

Been.

Nov.

4, 1979 — More than 3,000 Iranian militant students storm the U.S. Embassy

in Tehran, Iran, taking 66 Americans hostage and setting the stage for a

showdown with the United States.

April 25, 1980

— A defining moment for President Jimmy Carter, for the American people

and for America’s military. At 7 a.m. a somber President Carter announces

to the nation, and the world, that eight American servicemen are dead and

several others are seriously injured, after a super-secret hostage rescue

mission failed.

April 26, 1980

— Staff Sgt. J.J. Beyers lies unconscious in a Texas hospital bed. The

Air Force radio operator was one of the lucky few C-130 aircrew members to

survive a ghastly collision and explosion between his aircraft and a helicopter

on Iran’s Great Salt Desert. The accident took place after the rescue

team was forced to abort its mission at a location from then on known as

Desert One.

The

living room walls in J.J. Beyers’ Florida home tell a story of intense

pride and patriotism — a shrine to days and friends long past. The dark

paneling in this modest, single-story house is the canvas for a riveting

collection of photos, citations and plaques. Although faded over the years,

the collection possesses an unspoken power.

Beyers’ hands

and arms tell another side of the story. Settling into his favorite recliner,

the former Air Force sergeant rolls up the sleeves of his checkered shirt.

The scars on his arms and his disfigured hands tell their own harrowing tale.

Even after all these years, the tale of courage, hope, pain, fear and

disappointment jump out and scream, listen!

In 1980, Beyers

was part of an elite group of airmen, soldiers, sailors and Marines who

volunteered for Operation Eagle Claw — a bold and daring rescue attempt

of Americans held hostage in Tehran, Iran.

Beyers’ scars

and mementos are emblematic of the rescue mission. They’re constant

reminders of the friends he lost. A reminder of the disaster he survived.

A reminder of what could’ve been.

“I was

lucky,” Beyers said. “I lived.”

Five of his crewmates

from the 8th Special Operations Squadron at Hurlburt Field, Fla., died in

the Iranian desert, along with three Marine helicopter crewmen.

“They were

a brave, courageous and determined group of guys,” Beyers said. “I

miss them.”

Countdown to tragedy

The countdown to Desert One began in spring 1979 when a popular uprising

in Iran forced longtime Iranian ruler, Shah Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, into exile.

After months of internal turmoil, the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeni, a Shiite

Muslim cleric, took power in the country.

On Nov. 4, 1979,

just a few weeks after President Jimmy Carter allowed the Shah to enter the

United States for medical treatment, thousands of Iranian students stormed

the American Embassy in Tehran, taking 66 hostages and demanding the return

of the Shah to stand trial in Iran.

American diplomatic

efforts to release the hostages were thwarted by Khomeni supporters. At the

same time, Pentagon planners began examining rescue options.

Planning a rescue

The original intent was to launch a rapid rescue effort. But, every

quick-reaction alternative was dismissed. For planners, the situation was

bleak. Intelligence information was difficult to get. The hostages were heavily

guarded in the massive embassy compound. Logistically, Tehran was a city

crammed with 4 million people, yet it was very isolated — surrounded

by about 700 miles of desert and mountains in every direction. There was

no easy way to get a rescue team into the embassy.

One scenario was

parachuting an elite Army special forces team in. The team would fight its

way in and out of the embassy, rescuing the hostages along the way. That

plan was deemed suicidal.

After

realizing there was no infrastructure or support for a quick strike, planners

started mapping out a long-range, multifaceted rescue.

What emerged was

a complex, two-night operation. An Army rescue team would be brought into

Iran with a combination of helicopters and C-130s. The “Hercs”

would fly the troopers into a desert staging area from Oman. They would load

the rescue team on the helicopters, refuel the choppers, and then the helos

and shooters would move forward to hide in areas about 50 miles outside

Tehran.

On day two, the

Army team would be escorted to the embassy in trucks by American intelligence

agents. The Army team would take down the embassy, rescue the hostages and

move them to a nearby soccer stadium. The helos would pick up the shooters

and hostages at the stadium and evacuate them to Manzariyeh Air Base, about

40 miles southeast of Tehran.

MC-130s would fly

Army Rangers and Combat Controllers into Manzariyeh. The Rangers would take

the field and hold it for the evacuation. Meanwhile, AC-130H Spectre gunships

would be over the embassy and the airfield to “fix” any problems

encountered. Finally, C-141s would arrive at Manzariyeh to fly the hostages

and rescue team to safety.

Secrecy and surprise

were critical to the plan. The entire mission would be done at night, and

surprise was the Army shooters’ greatest advantage.

It was an ambitious

plan; some say too ambitious.

“This mission

required a lot of things we had never done before,” said retired Col.

(then-Capt.) Bob Brenci, the lead C-130 pilot on the mission. “We were

literally making it up as we went along.”

Flying using

night-vision goggles was almost unheard of. There was no capability, or for

that matter, a need, to refuel helicopters at remote, inaccessible landing

zones. All these skills and procedures would be tested and honed for this

mission.

“These

capabilities are routine now for special operators, but at the time we were

right there on the edge of the envelope,” said retired Col. (then-Capt.)

George Ferkes, Brenci’s co-pilot.

The aircrews

weren’t the only ones pushing the envelope. Airman First Class Jessie

Rowe was a fuels specialist at MacDill Air Force Base, Fla., when he got

a late night call to pack his bags and show up at the Tampa International

Airport. He met his boss, Tech. Sgt. Bill Jerome, and the pair flew to Arizona.

They were now a part of Eagle Claw. Their job? Devise a self contained refueling

system the C-130s could carry into the desert to refuel the helicopters at

the forward staging area.

“No one told

us why,” said Rowe, who’s now a major at Hurlburt Field and one

of just two operation participants still on active duty. “But, you

didn’t need to be a rocket scientist to figure it out.

“We begged,

borrowed and stole the stuff we needed to make it work,” he said. “We

got it done. In less than a month, we had a working system.”

The Eagle Claw

players were spread out, training around the world. The Hurlburt crews spent

most of their time training in Florida and the southwestern United States.

The pieces were coming together.

At the same time,

negotiations to free the hostages continued to go nowhere. By the time April

1980 rolled around, the Eagle Claw team had been practicing individually,

and together, for five months. The aircrews averaged about 1,000 flying hours

in that time. In comparison, a typical C-130 crew dog would take three years

to log 1,000 hours.

It’s showtime

“We were chomping at the bit,” Brenci said. “We just wanted

to go and do it.”

After a long training

mission in Arizona and a flight to Nellis Air Force Base, Nev., to pick up

parts, Col. J.V.O. Weaver (a captain then) and his crew, returned to Hurlburt

Field to an unusual sight.

“We rolled

in and noticed the maintenance guys were on the line painting all the birds

flat black,” Weaver said. “They painted everything. Tail numbers,

markings. Everything.”

The plan was moving

forward. Less than a day later, six C-130s quietly departed Florida bound

for Wadi Kena, Egypt. The president hadn’t pulled the trigger yet, but

the hammer was cocked on the operation.

The Army and Air

Force troops were in Egypt awaiting orders. The Marines and sailors, the

helicopter contingent, were aboard the USS Nimitz afloat in the Persian Gulf

off the coast of Iran.

“I remember

we ate C-rats (the predecessor to MREs) for days and then one morning a truck

rolls up, and we’re served a hot breakfast,” Rowe said. “Light

bulbs went on in everyone’s minds.”

The hot breakfast

was a precursor to a briefing and pep talk from Army Maj. Gen. James Vaught,

the Joint Task Force commander for Eagle Claw. The mission was a go.

“Everyone

was pumped up,” said retired Chief Master Sgt. Taco Sanchez (then a

staff sergeant). “Arms were in the air. We were ready!”

Next stop, Masirah.

A tiny island off the coast of Oman. To say this air patch was desolate would

be kind. It was a couple of tents and a blacktop strip. It was the final

staging area — the last stop before launching.

Just before sunset

on April 24, Brenci’s MC-130 took off toward Desert One. The die was

cast. Brenci’s crew would be the first to touch down in Iran. They carried

the Air Force combat control team and Army Col. Charlie Beckwith’s

commandos. Beckwith would lead the rescue mission into the embassy. Also

on board Brenci’s plane was Col. James Kyle, the on-scene commander

at Desert One and one of the lead planners for the operation. The other Hercs

left Masirah after dark, and the helicopters launched off the Nimitz.

It was a four-hour

flight. Plenty of time to contemplate what they were attempting.

“We just tried

to stay busy,” Sanchez said. “We were in enemy territory now. The

pucker factor was pretty high.”

The first challenge

would be to find the make-shift landing strip. Only 21 days earlier, Maj.

John Carney, a Combat Controller, had flown a covert mission into Iran with

the CIA to set up an infrared landing zone at Desert One. Carney was perched

over Brenci’s shoulder as the C-130 neared the landing site. The lights

he had buried in the desert would be turned on via remote control from the

C-130’s flight deck. The question was, would they work?

Brenci was a couple

miles out when in slow succession a “diamond-and-one” pattern appeared

through his night-vision goggles. The bird touched down in the powdery silt,

and the troops went to work.

Gremlins arrive

The choppers, eight total, left the Nimitz and were supposed to fly formation,

low level, to the meet area. Because of the demands of the mission, at least

six helicopters were needed at Desert One for the mission to go forward.

Two hours into the flight the first helicopter aborted.

Further inland,

the Marine helo pilots met their own private hell. Weather for the mission

was supposed to be clear. It wasn’t. Flying at 500 feet, the helicopters

got caught in what is known in the Dasht-e-Kavir, Iran’s Great Salt

Desert, as a “haboob” — a blinding dust storm. The situation

was bad. After battling the storm for what seemed like days, one of the

helicopters turned back.

At Desert One,

all the C-130s had landed and were taxied into place. They were waiting for

the choppers. An hour late, the first helicopter arrived.

“We weren’t

on the ground that long, but my God, it felt like an eternity waiting for

the helos,” Beyers recalled. The first two helicopters to roll in pulled

up to Beyer’s aircraft to be refueled. When the sixth chopper showed,

everyone breathed a sigh of relief.

The Army troops

boarded the helicopters. The fuels guys did their magic. Everything was good.

Then word spread. One of the helicopters had a hydraulic failure. Game

over.

Beckwith needed

six helicopters. Kyle, the on-scene commander, aborted the mission.

“It was

crushing,” Rowe said. “We had come all that way, spent all that

time practicing, and now we had to turn back.”

The decision made,

now the crews had to evacuate the Iranian dust patch. Time was a factor.

The C-130s were running low on fuel. Sunrise was fast approaching, and the

team didn’t want to be caught on the ground by Iranian troops. Members

had already detained a civilian bus with 40-plus passengers and were forced

to blow up a fuel truck, which wouldn’t stop for a roadblock.

They had worn out

their welcome. Dejected and disappointed, they just wanted to button up and

go home.

Beyers’ aircraft,

flown by Capt. Hal Lewis, was critically low on fuel. But, before it could

depart, the helicopter behind the aircraft had to be moved.

“We had just

taken the head count,” recalled Beyers. They had 44 Army troops on board.

Beyers was on the flight deck behind Lewis’ seat. “We got permission

to taxi and then everything just lit up.”

A fireball engulfed

the C-130. According to witnesses, the helicopter lifted off, kicked up a

blinding dust cloud, and then banked toward the Herc. Its rotor blades sliced

through the Herc’s main stabilizer. The chopper rolled over the top

of the aircraft, gushing fuel and fire as it tumbled.

Burning wreck

Fire engulfed the plane. Training kicked in. The flight deck crew began shut-down

procedures. The fire was outside the plane. Beyers headed down the steps

toward the crew door. That’s when someone opened the escape hatch on

top of the aircraft in the cockpit, Beyers said. Boom. Black out.

Tech. Sgt. Ken

Bancroft, one of three loadmasters on the airplane, knew he had troops to

get off the plane. He went to the left troop door. Fire. Right troop door.

Jammed shut.

“I don’t

know how I got that door off,” Bancroft said.

He did. One after

another, this hulk of a man tossed the Army troops off the burning plane

like a crazed baggage handler unloading a jumbo jet.

Beyers had been

knocked out. The flight deck door had hit him on the head as he went down

the steps. When he came to, he was on fire. Conscious again, he crawled toward

the rear of the plane.

“I made it

halfway,” Beyers said. “I quit. I knew I was dead.” Somehow

he moved himself closer to the door. Then he saw two figures appear through

the flames. Two Army troopers had come back for him. He was alive, but in

bad shape.

Beyers always had

the bad habit of rolling up his flight suit sleeves. He finally paid the

price. His arms, from the elbows down, were terribly burned. His hands were

charred. Hair, eyebrows and eyelashes, gone. Worse were the internal injuries.

His lungs, mouth and throat were burned. Yet, he clung to life.

The desert scene

was one of organized chaos. Failure had turned to tragedy.

“I knew they

were dead,” Bancroft said of his crew mates in the front of the plane.

“I looked up there, and it was just a wall of fire. There was nothing

I could do.”

The last plane

left Desert One a half hour after the accident. Beyers was on that

airplane.

“The accident

was a calamity heaped on despair. It was devastating,” wrote Kyle in

his book called “The Guts to Try.”

“The C-130

crews and Combat Controllers had not failed in any part of the operation

and had a right to be proud of what they accomplished,” Kyle said.

“They inserted the rescue team into Iran on schedule, set up the refueling

zone, and gassed up the helicopters when they finally arrived. Then, when

things went sour, they saved the day with an emergency evacuation by some

incredibly skillful flying. They had gotten the forces out of Iran to fight

another day — a fact they can always look back on with

pride.”

Pride and sorrow

are the two mixed emotions most participants share.

“We were the

ultimate embarrassment,” Sanchez said. “Militarily we did some

astounding things, but ultimately we failed America. I’m proud of what

we accomplished. I was 27 years old, and when I think about that mission

it still sends shivers down my spine.”

The aftermath of

the rescue operation was a barrage of investigations, congressional hearings

and, believe it or not, more planning and training for a follow-on rescue

mission.

Members of the

8th SOS were involved in those plans. In fact, some of the same crew members

who participated in Eagle Claw came back and started preparing for the follow-up

mission.

Healing the wounds

At the same time, the squadron needed to bury its dead, and start healing

the wounds from Desert One. Beyers survived the tragedy. After spending a

year in the hospital, and enduring 11 surgeries, he was medically separated

from the Air Force.

The bodies of the

eight men were eventually returned to the United States, and a memorial service

was held at Arlington National Cemetery.

Memories of that

ceremony are still vivid for many of the rescue team. Weaver, who was an

escort officer, still recalls when President Carter visited the families

prior to the service. After talking with a Marine family, the president made

his way to the family Weaver was escorting.

“He came up

to the family, then he looked down at those two little boys, and he just

got down on his knees and wrapped his arms around them,” Weaver said.

“Tears were streaming down his cheeks. Here’s the president of

the United States, on his knees, crying, holding these boys. That burned

right in there,” he said pointing to his chest.

A memorial was

placed at Arlington National Cemetery honoring the eight men killed.

Subsequently, other tributes have been made remembering the men who died

at Desert One. Hurlburt has dedicated streets in their honor. New Mexico’s

Holloman Air Force Base Airman Leadership School is named for Tech. Sgt.

Joel Mayo, the C-130 flight engineer killed at Desert One.

Mayo and Sanchez

were good friends. “I talked to him that night,” Sanchez said,

flashing back to a time long ago. “It’s important people understand.

Joel had no idea he was going to give his life that night. But, if you told

him he was going to die, he still would’ve gone.”

Sanchez’s

words capture the essence of every man on the mission. They were a brave,

courageous group of men, attempting the impossible, for a noble and worthy

cause. They came up short and have lived 21 years with the demons, or gremlins,

that sabotaged their mission of mercy.

“They tried,

and that was important,” said Col. Thomas Schaefer, the U.S. Embassy

defense attaché and one of the hostages. “It’s tragic eight

men died, but it’s important America had the courage to attempt the

rescue.”

In his living room,

Beyers gazes at the photos on his wall. Pointing to the picture of his crew,

he says, “How I survived and they didn’t, I don’t know. I

was lucky.”

Even having lived

so long with the horrible outcome of that mission, Beyers never doubts his

choice to take part.

“We do things

other people can’t do,” he said. “We would rather get killed

than fail. It was an accident. But, I have no doubt, had the Army guys gotten

in there, we would’ve succeeded.”

It comes down to

that. Desert One is a story of what could’ve been.

|