|

|

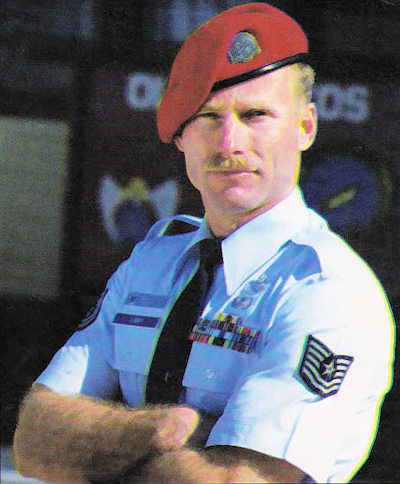

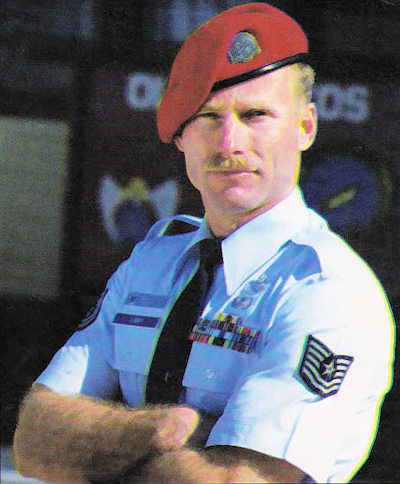

| Airman's Portrait; Presenting a member of Air Force's worldwide family each month. |

"Combat Controllers are the first people to employ into an assault zone — ahead of the main strike force.

Once there, they have

absolute air traffic control responsibility

for all aircraft flying into or through the zone.

The challenges and responsibilities

are enormous — and rewarding."

TSgt Dave Libby

Instructor,

Combat Control/Pararescue

Indoctrination Course

Lackland AFB,Texas

|

Born: Aug. 6, 1955, Santa Monica, Calif.

Enlisted: June 29, 1979, Ventura, Calif.

Career: Master parachutist,

HALO (exits high altitude but opens chute low)

jump master,

scuba dive supervisor,

air traffic controller;

qualified in demolition.

Tours at Norton AFB, Calif. (1980-82), and

Howard AB, Panama (1982-87). |

|

Journey to Isikveren Hot. Dusty. Desolate. And in the midst of desolation, a hubbub of frantic activity.

This

is how Dyarbakir, Turkey, appears to the Airman team as we arrive by

C-130 from Incirlik AB at a tent city erected to sustain Operation

Provide Comfort. Comfort, perhaps, for the Kurdish refugees the

operation supports, But scant comfort for the soldiers, sailors, airmen

and Marines gathered here. Or for the dozens of multi-national military

and civilian aircrews whose planes crowd the airstrip. It's not a place

where one lingers.

And

so after a restless night' s sleep in a tent not 100 feet from the

runway — and frequently swept with a thick, clinging, brown dust

from the backwash of C-130 props— we continue our journey.

The

way out of Dyarbakir. if you're traveling southeast to the sprawling

Kurdish refugee camp at Isikveren, is by road or air. We choose

air — an MH-53J Pave Low helicopter of the Air Force Special

Operations Detachment Deployed.

The

unit is part of a conglomeration of special ops components temporarily

headquartered at Incirlik AB: 39th Special Operations Wing, Rhein-Main

AB, Germany; 21st Special Operations Squadron, RAF Woodbridge, England;

20th Special Operations Squadron, Hurlburt Field, Fla.; and the 1550th

Combat Crew Training Wing, Kirtland AFB. N.M.

Special

Operations has been involved in Provide Comfort from the operation's

earliest hours. In fact, a 39th SOW MC-13Q, based at Incirlik, made the

first air drop of food for Kurdish refugees.

Used

to flying classified missions, the MH-53J aircrews at Dyarbakir enjoy

the more relaxed nature of their current taskings. Assignments include

low weather reconnaissance, scouting established refugee camps in

Turkey and potential relocation sites in Iraq, air-dropping food and

water, and moving troops to and from the camps.

The

troops they carry are mainly members of Special Forces Assessment

Teams. Each team has some 60 members, including soldiers; Air Force

pararescuers from Detachment 1. 1723rd Special Tactics Squadron, RAF

Woodbridge; and Combat Control teams from Rhein-Main. Pave Low choppers

are their only link to civilization — or Dyarbakir, the nearest

thing to it. And our only link to them.

As

the MH-53J slips down a river valley, we pass ancient ruins and modern

villages that appear almost as ancient. From a few hundred feet up.

south-em Turkey looks like much of the American southwest. A parched,

hostile land.

But

from the treacherous Turkish mountainsides come not the forked, darting

tongues of rattlesnakes. Instead, the lamenting wails of sick, hungry,

exhausted Kurds. Not the pincers of scorpions, but the outstretched

hands of refugees, craving food and water, medical aid, and friendship.

On

an unfriendly slope at the Turkey-Iraq border, American forces of war

have come in peace. The Americans bring relief to these uprooted, weary

and frightened people. The cause is humane, the effort herculean.

Combat Controller SSgt. Stacey Poland vectors the MH-53J to a soft, dusty

landing at Isikveren — within eyesight of Iraq. He watches as we

rush down the ramp, our bags, cameras and tape recorder in hand. He's

all business as he grabs one of our bags and says, "Follow me."

"There's

a German 'Huey' you can probably ride to the refugee camp." he tells

us. Within minutes, we're on the small chopper, being whisked to the

largest refugee camp in Turkey.

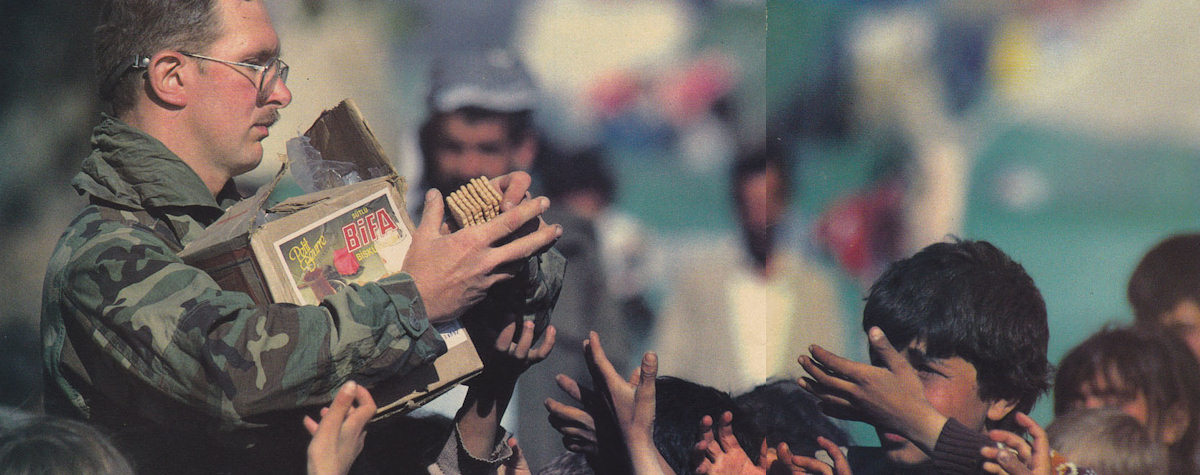

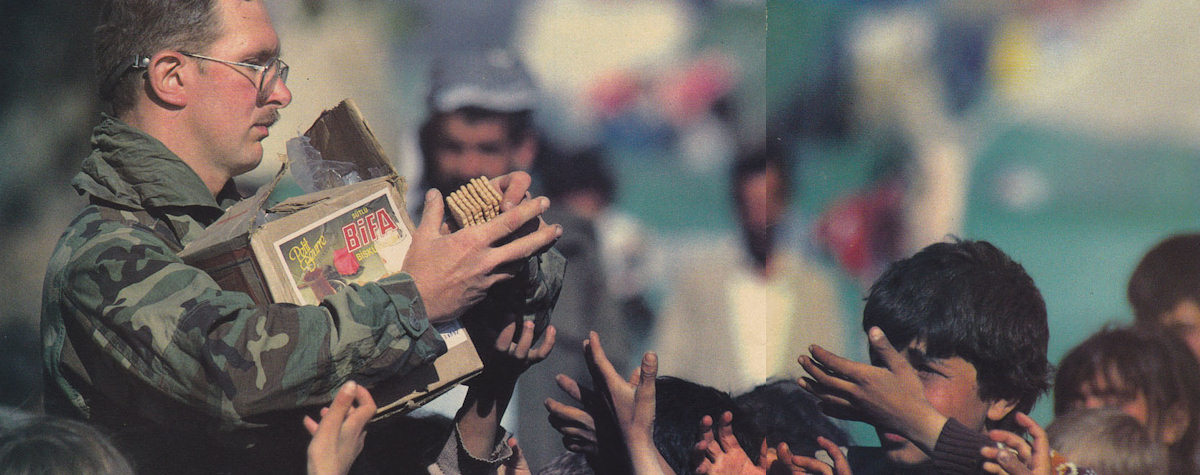

"Organization

was the biggest problem when we arrived here," Sergeant Poland says.

"There were so many Kurds and so few of us, we were having trouble

distributing food and water to them."

With

the help of interpreters, the quick reaction force learned there

were 17 Kurdish tribes in the camp. They began distributing food to

tribes according to their numbers. The upper landing zone became a

supermarket of sorts, and the American forces dubbed it "Piggly Wiggly."

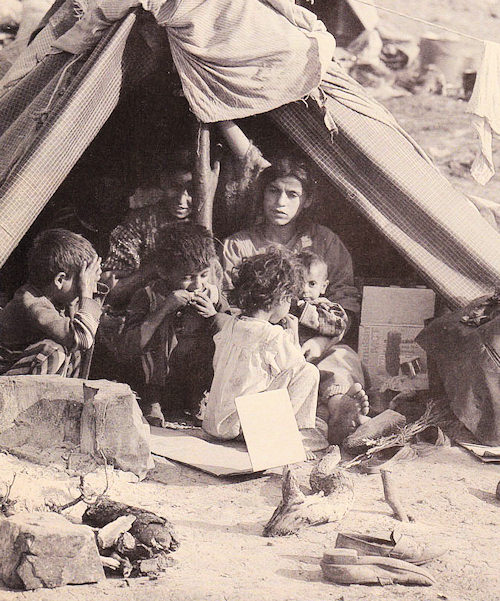

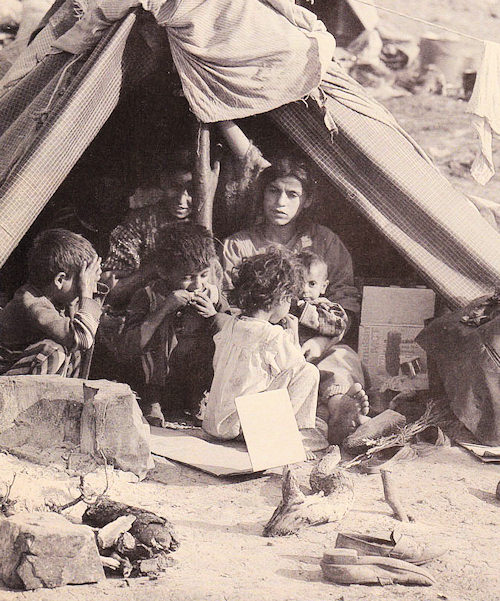

Right; A single

tent provides shelter for six women and children.

What

remained after they licked the food problem was a much deadlier menace:

sanitation. "At first, dozens of people died every day." Sergeant

Poland says. (During the 24 hours Airman spends at Isikveren. there are

two burials.)

MSgt.

Emilio Jaso high-fives a youngster as he strides purposefully along a

twisted trail through a maze of tents, cooking pits and the

ever-present throng of children. The senior Air Force representative at

Isikveren, he works closely with special forces troops — "SF's"

— manning a medical aid station, while Combat Controllers and

SF's control food and water distribution.

"I

know we've turned the corner on first aid, because we're getting people

who want treatment for old ailments and minor aches and pains."

Sergeant Jaso says. "But there's still a lot of dysentery and diarrhea,

because the people don't properly wash their pans and utensils.

|

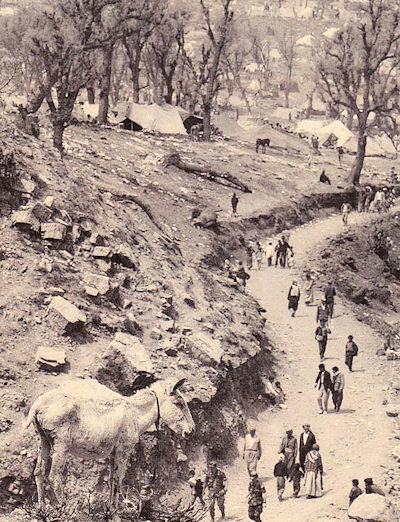

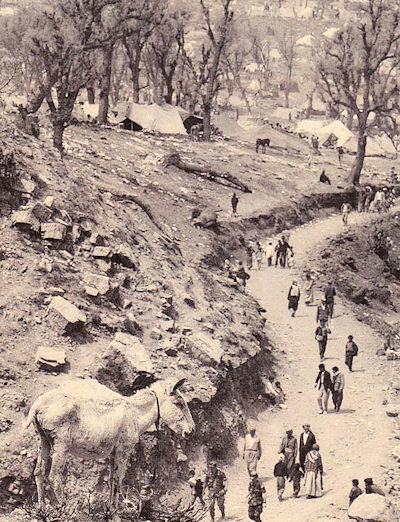

Suddenly,

we're in a different — and alien — world. The stench of

smoke, food, rotting flesh, human and animal excrement assaults our

nostrils. The din of thousands of voices and scores of trucks, jeeps,

motorcycles and helicopters rings in our ears. The braying of donkeys

rises above the cacophony and seems oddly out of sync.

Smoke

from cooking fires (left) casts an eerie pall over the 60,000

temporary residents of Isikveren.

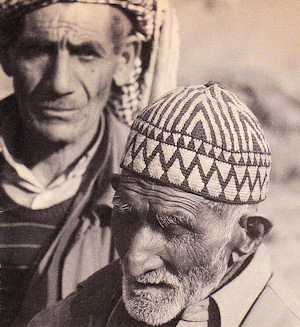

We

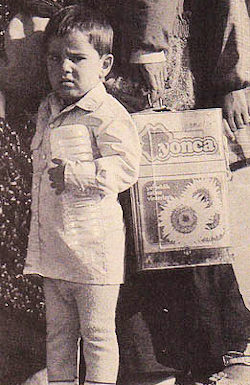

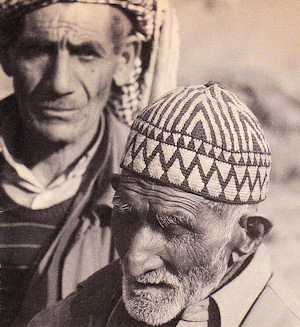

feel crushed — physically, by the relentless push of children

begging for a handout or handshake ("Mister, take picture. Mister,

cigarette?") — emotionally, by the staring eyes of old men. the

coquettish looks of young women, the eager smiles of children.

So

many children. They latch on to the Americans. "Hello. Hello. Hello.

Mister, take picture?" While their parents, grandparents and older

siblings ask for food, water and medical aid. And wait.

A man and his father (right), suffering

etched on their faces, quietly spend another day at the camp. |

|

|

|

We're

trying to teach them proper sanitation, and those we've taught are

staying reasonably healthy."

Sergeant

Jaso's Kurdish interpreter, Maged, recruits Kurdish doctors and nurses

to help staff the aid station and dispense medicine.

|

As

time passes, more and more civilian agencies around the world pour in:

CARE. Doctors Without Boundries, Red Cross and its Islamic

counterpart. Red Cresent, UNICEF and others. But more than half the the

medical supplies and medicines come from U.S. military stocks.

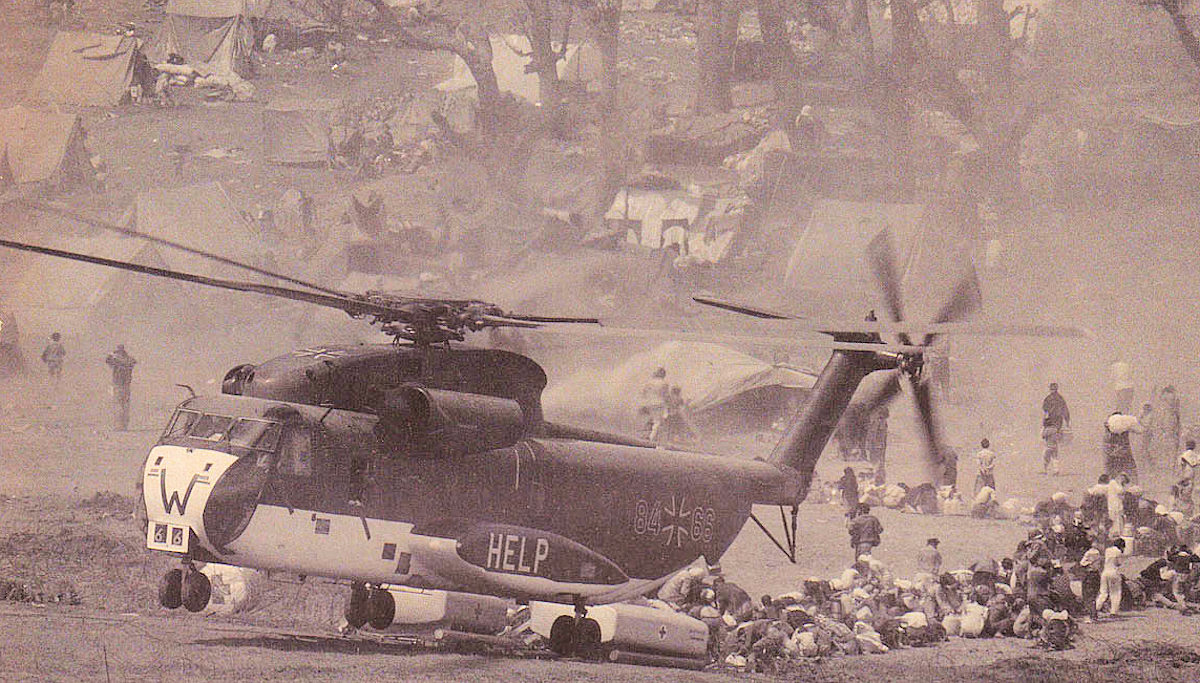

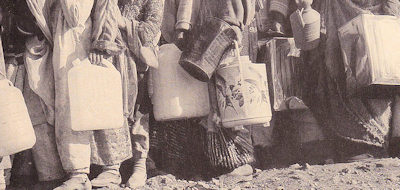

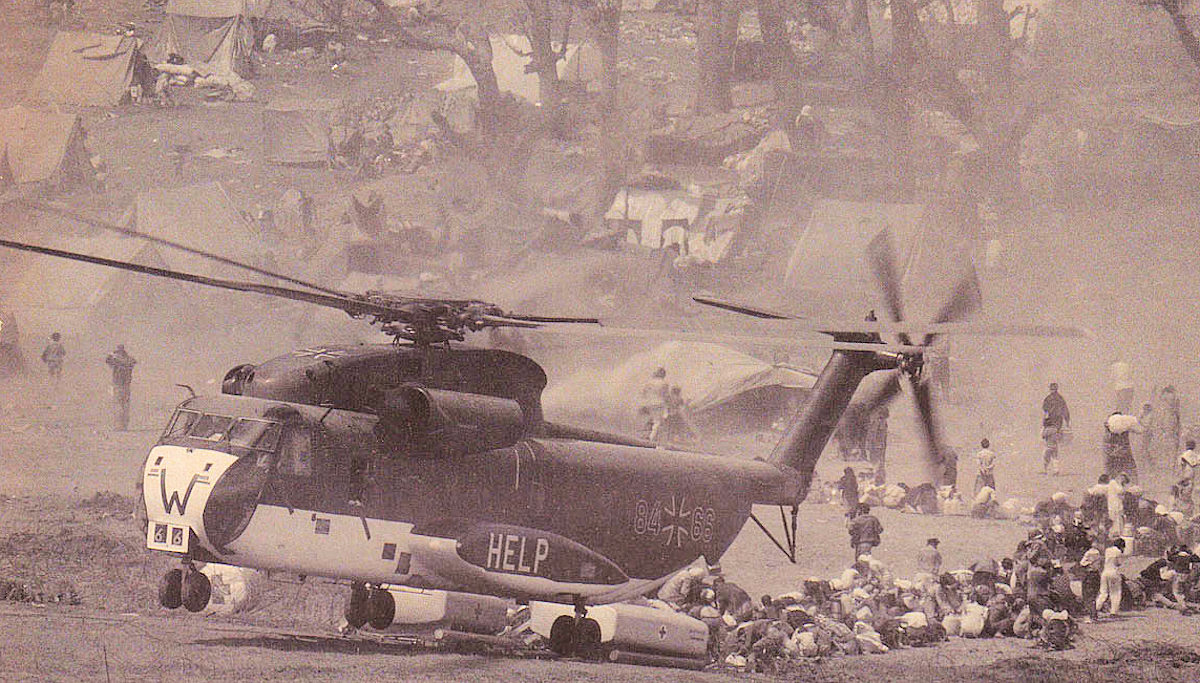

The

Turkish government provides truckloads of bottled water, while every 45

minutes, a German helicopter delivers a huge bladder of water that its

crew pumps into galvanized tanks.

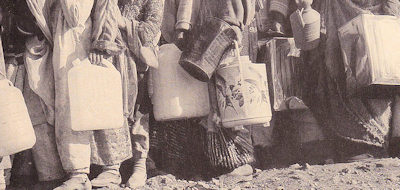

Distributing

the bottled water is hazardous duty. Kurds mob the trucks and are

sometimes injured in the melee. |

|

A German

helicopter (above) brings water to the camp. Refugees toting containers

line up for fresh water.

|

Typically, SF's move in to break up the

crowds and attempt to establish order. Strong-arming the clamoring men,

the SF's force the mob back, then attempt an orderly distribution.

Observing

such a scene, pararescuer TSgt. Rod Alne shakes his head. "I don't know

why they still rush the trucks," he says. "Everyone in the camp is

getting enough food and water. I think it's become a game to them."

|

| Or

a way to break the monotonous cycle of days since they crossed the

snow-crested mountain to escape persecution and death. Each morning at dawn, a

smoky shrouds the camp as women and children prepare breakfast of

unleavened bread. By 8 a.m., the same women and children are lined up at the

galvanized tanks with cans, jugs and bottles. At 10, men representing each tribe begin

gathering for the 11 o'clock food distribution. |

Kurdish

women (right) bake bread — perhaps the only meal their family

will eat that day.

Donkeys and people walk the dusty trail (left) that

snakes its way through the huge camp.

The remainder of the day is

activity and lulling about puncl medical emergencies, crying children and

funerals. Those needing medical form a line at the American aid station and at

other medical tents springing up staffed by medical teams from a host

of nations.

|

|

Sergeant

Jaso is constantly sought. "We need medicine," pleads a German doctor.

"This woman will have to be taken to a hospital," determines a Kurdish

physician." To each, Sergeant Jaso and other team members respond

quickly and positively.

Meantime,

Combat Controllers handle a steady flow of chopper traffic to and from

the LZ. With each arrival, the Kurds gather hopefully. Each time, they

are stung by flying grit and pebbles as the chopper's whirling blades

whip the air.

|

|

And

then it's dusk, and the acrid smell and haze of cooking fires return.

As the Americans head downhill on motorcycles and trucks, thousands of

Kurds line the twisting din road seeking high-fives and shouting

"Hello. Hello. Mister, take picture?" grime

from their faces and hands and prepare meals. A few sit alone on cots,

trying to shrug off a day of images that years will not erase.

|

Maj.

David Bissell thinks the Isikveren camp won't need his team

much longer. "Our job was to establish an

organized camp to provide fair and equitabte distribution of food

and water," says the commander of A Company, 1st Battalion, 10th Special Forces Group. "We've done that.

"Now,

we'll send 250 Kurdish men each day back to Zakhu, the Iraqi city where

the majority of these people came from. Military coordinators are

there, and once they say the camp is ready, we'll begin sending

families back." (At press time, the relocation process had begun.)

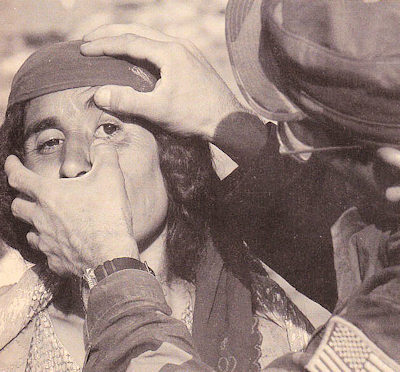

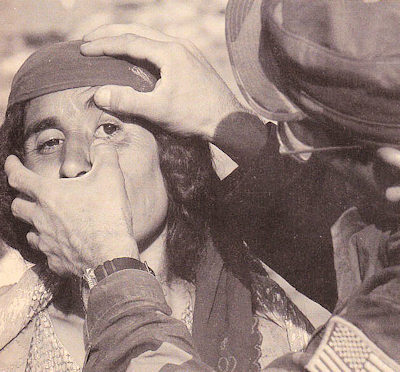

MSgt.

Emilio Jaso (left), pararcscueman, delivers medical supplies to an

aid station he helped establish at the refugee camp.

Sergeant Emilio Jaso examines an eye infection (right). The Kurds call

him, other pararescuemen and special forces members "Doctor" because

they dispense tionprescription medicine and first aid.

The

major says civilian relief agencies are poised to take over full

operation of the Isikveren camp. When this happens, his team also will

move to Zakhu to oversee the resettlement of the Kurdish refugees.

|

|

Next

day, Sgt. Brian Hall mans the field phone at the upper landing zone,

controlling inbound helicopters. At mid-morning, several open-bed

trucks depart the LZ. laden with the first 250 Kurds returning to Iraq.

An SF rides shotgun on the roof of each truck cab.

|

|

As

soon as the last truck leaves the LZ, two SF's pull a coil of

concertina wire across the gate, barring refugees from rushing the

orderly stacks of boxes containing food supplies for the morning's

distribution.

Just

before the food distribution begins. Sergeant Hall takes a call from an

inbound MH-53J. "You got two guys from Airman magazine looking for a

ride?" the pilot asks. "Sure do," he responds.

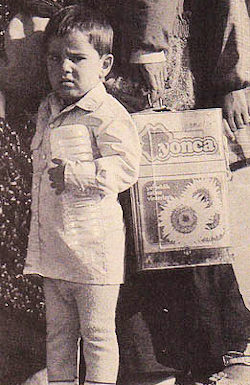

Right; a Kurdish youngster finds temporary joy posing for a picture.

In

minutes, the chopper's huge blades again whip up grit and tiny stones,

forcing the handful of GIs and thousands of refugees in and around the

LZ to turn their backs and protect their faces from the shower of

flying debris.

Quickly,

we're on the bird and circling for one last look, high above the

be-tented and trash-strewn mountainside. From above — beyond the

reach of children's clinging hands and the myriad odors of the living

and dying — the camp seems surrealistic-ally peaceful, almost

still.

Then

we're over the next valley and the terrain is again empty of human

habitation. In an hour, we're back at Dyar-bakir and within two hours,

we're on a C-130 bound for Incirlik AB, 90 minutes away.

With

us on this final leg of our journey to Isikveren: the casketed body of

a U.S. Marine, killed in an accident while providing refugee relief.

Words come to mind: 'He died that others might live." Mean-ngful and

true.

Briefly, I mourn for my fallen comrade. Silently I thank him.

Special thanks to J.C. Cummings for sending this article

|

|

|

Next

day, Sgt. Brian Hall mans the field phone at the upper landing zone,

controlling inbound helicopters. At mid-morning, several open-bed

trucks depart the LZ. laden with the first 250 Kurds returning to Iraq.

An SF rides shotgun on the roof of each truck cab.

Next

day, Sgt. Brian Hall mans the field phone at the upper landing zone,

controlling inbound helicopters. At mid-morning, several open-bed

trucks depart the LZ. laden with the first 250 Kurds returning to Iraq.

An SF rides shotgun on the roof of each truck cab.