|

KEESLER

AIR FORCE BASE, Miss. — The reminders are constant. They're painted on

the walls of the exclusive gym, screamed by instructors during intense

physical training. Never quit.

To exit the Combat Controller

training building here, trainees must tap a sign with that message.

Massive letters inscribed on the walls inside the building — NFQ —

represent the "no quitters" mantra, with an expletive added for

emphasis.

Still, about 60 percent of the airmen who come to the

Combat Control Operator Course will quit, putting additional pressure

on a specialty known for its difficulty in recruiting and retaining

airmen.

To

announce to their classmates that they are finished, trainees must ring

a silver bell in the gym. The message: They can't handle the training.

This isn't for them.

When they walk out for the last time, they don't tap the writing above the door.

"You

can only quit once," said Master Sgt. Brad Reilly, the non-commissioned

officer in charge of Combat Controller training at Keesler. |

|

Critical skills

The

four-month stay at Keesler is one step in a long journey to becoming an

Air Force Combat Controller. Controllers are attached to the military's

elite special operations groups, such as Army Special Forces or Navy

SEALs, and are trained to direct aircraft and set up operating

airfields.

But as cool as the job might sound, it requires special skills that are

hard to find — and even harder to retain. Combat Control is one

of the Air Force's most critically understrength career fields, with a

retention rate of about 13 percent in 2011.

|

But there are incentives: Airmen

in these jobs who have 17 months to 14 years of service are eligible

for the top re-enlistment bonuses — up to $90,000 this year. And they

typically have higher promotion rates than other specialties.

The

Air Force's approximately 500 Combat Controllers also are considered to

be in a stressed career field because of their high deployment rates

and operational tempo, and there's no sign of that easing up.

Left;

Air Force Combat Controllers set up communications to contact the

special tactics operation center while conducting a drop zone survey in

Port-au-Prince, Haiti, on Jan. 24,2010, during Operation Unified

Response. Combat Control is one of the Air Force's most critically

undermanned career fields.

|

"We

still and always will remain an undermanned career field," Reilly said.

"We've just got to find the raw material first ... find somebody who

wants to do this. Not many guys in the Air Force want to do this."

To

help identify airmen with the desire and ability to withstand intense

training, a Rand study commissioned by the Air Force to help improve

retention among nine critical skills recommended using the

emotional-quotient inventory, or EQ-i test, as part of the screening.

The service is working on incorporating the test, according to the

study.

Getting started

Selection for Combat Controllers begins with a 10-day course after basic military training at Joint Base San Antonio-Lackland.

"It's a kick in the balls,"

Reilly said, meant to weed out those who aren't ready. This phase has a

35 percent to 50 percent attrition rate.

The instructors at Keesler get

their chance with the trainees next for about four months of intense

physical training and classroom work. From there, they move to training

back at Lackland and on to bases such as Fairchild Air Force Base,

Wash.; Hurlburt Field, Fla.; and Pope Field, N.C., for courses that

include survival, evasion, resistance and escape training; jump

training — including high-altitude, low-opening — and

combat dive training.

The trainees work for 35 weeks

before they earn the scarlet beret that comes with being a Combat

Controller. Then they move on for more advanced training.

Physically grueling

|

Training days at Keesler are

long, and start hard. Combat trainees are up before 5 a.m. every day

for their gym and beach workouts.

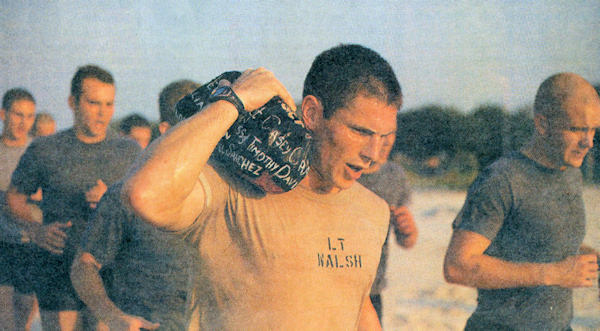

On a morning in late June, a

group of 11 trainees met in the combat-exclusive gym on base to prepare

for a grueling two hours on the sandy beaches of Biloxi, Miss.

At

6 a.m., the Blue Bird bus pulled up to Highway 90, a stretch of beach

on the coast situated between two massive luxury hotels. Two by two,

the 11 ran to the beach, with Lt. Christopher Walsh in front. On his

right shoulder he carried a painted rock, about the size of a

basketball, with the names of fallen Combat Controllers. Each training

group gets one, and they hold onto it and take care of it during their

time at Keesler.

Over the next two hours, they were pushed to

their limit, with multiple 600-meter sprints, and then even more

sprinting intervals.

|

| First

Lt. Christopher Walsh carries a rock painted with the names of fallen

Combat Controllers during a morning FT run in Biloxi, Miss. Each team

of trainees traditionally carries a similar rock through their time at

the Combat Control Operator course at Keesler Air Force Base. |

With barely a rest, they moved to soft sand for

more sprints, firemen's carries, buddy drags and burpees — a

combination pushup and jumping jack done countless times throughout the

day. Two trainees who had fallen behind the others were even ordered to

do them in the ocean.

For about half of the exercises, the

trainees competed with one another. For the other half, they worked

together and carried each other to make it through.

"They run together; it's good that they push each other," Reilly said.

When they finished, they cleaned the gym until it was pristine.

From there, they began a full day of air traffic control classes, alongside other airmen training to be air traffic controllers.

The five-phase class work at Keesler uses massive, expensive radar and

tower simulators to familiarize the airmen with tower operations. They

direct simulated airframes, replicating the situa¬tions Air Force

Combat Controllers face in the towers, and skills they will need during

operations in the field.

Class work goes into the night, and trainees sleep barely six hours before getting up and doing it again.

By

the end of the four months at Keesler, they are all Federal Aviation

Administration-certified air traffic controllers. But for the combat

trainees, this is just the beginning.

The end result

Reilly

is there to push everyone through the training and weed out those who

can't cut it. After serving as a Marine for 12 years in maintenance,

Reilly said he wanted to try something new and went for Combat Control.

The Marine job "just wasn't

enough to satisfy me," he said while watching the trainees do sprints.

"I wanted a real mission change."

If he knew how hard the training

would be, he said, he might not have done it. But now — after six

deployments, earning the Silver Star in Afghanistan — he doesn't

want to do anything else. He became the NCO in charge of the training

in November.

Most trainees arrive straight out of basic training, young and determined to make the cut.

One is Philadelphia-native Airman

1st Class Dan Dalton. During the morning beach FT, he was up front,

leading the group through burpees on the sand and setting the pace in

several runs.

Going into training, he had an

idea of what he was getting into. But when it gets tough, the guys

around him are there to help push through, he said.

"I know I want to do the job," he

said. "I know it's going to be hard. But, it's doable. People who came

before me succeeded. When there's rough times, you just look to the guy

next to you and know that he's still going, so I'm still going to go."

Others

have taken different paths to becoming a Combat

Controller, or for officers, becoming a special tactics officer.

First Lt. Christopher Walsh was a

KG-135 maintenance officer at RAF Mildhenall, England, for 2 1/2 years

when he decided to earn the right to wear a scarlet beret. The idea of

special operations appealed to him, and he is now helping lead the

group through training as the only officer in his training group.

"It's just the end result,

knowing that one day you are going to be around heroes ... guys

downrange doing amazing things," he said. "You get to work with those

indi¬viduals. I think that is the most rewarding thing, especially

from a leadership perspective."